Little Big Man (film)

| Little Big Man | |

|---|---|

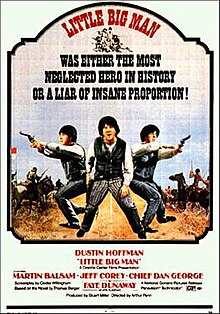

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Arthur Penn |

| Screenplay by | Calder Willingham |

| Based on | Little Big Man by Thomas Berger |

| Produced by | Stuart Millar |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Harry Stradling Jr. |

| Edited by | Dede Allen |

| Music by | John Hammond |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | National General Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time |

|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $15 million |

| Box office | $31,559,552 (domestic)[1] |

Little Big Man is a 1970 American revisionist Western film[2] directed by Arthur Penn, adapted by Calder Willingham from Thomas Berger's 1964 novel of the same title. It stars Dustin Hoffman, Chief Dan George, Faye Dunaway, Martin Balsam, Jeff Corey and Richard Mulligan. The film follows the life of a white man who was raised by members of the Cheyenne nation during the 19th century, and then attempts to reintegrate with American pioneer society. Although broadly categorized as a Western, or an epic, the film encompasses several literary/film genres, including comedy, drama and adventure. It parodies typical tropes of the Western genre,[3] contrasting the lives of white settlers and Native Americans throughout the progression of the boy's life.

Little Big Man is an early revisionist Western[2] in its sympathetic depiction of Native Americans, and its exposure of the villainous practices of the United States Cavalry. The revision uses elements of satire and tragedy to examine prejudice and injustice. Little Big Man is an anti-establishment film of the period, indirectly protesting America's involvement in the Vietnam War by portraying the United States Armed Forces negatively.[4]

The film was released to American theatres by National General Pictures on December 23, 1970, to widespread critical acclaim and commercial success.[5] Several retrospective reviews have positioned Little Big Man as one of the best American films of the 1970s.[5] The film received three BAFTA Award nominations, including for Best Actor in a Leading Role for Hoffman. Chief Dan George received an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor, the first Indigenous North American actor to be nominated for an Oscar.[6]

In 2014, Little Big Man was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the Library of Congress, and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.[7]

Plot

[edit]This article's plot summary may be too long or excessively detailed. (May 2024) |

The film is framed with narration by 121-year-old Jack Crabb, who is telling his life story to a historian.[4] In 1859, 10-year-old Jack and his sister Caroline survive the massacre of their parents by the Pawnee, and are discovered by Shadow, a Cheyenne brave, who takes the siblings to his village. Caroline escapes, but Jack remains and is reared by the good-hearted tribal leader, Old Lodge Skins.[4] Jack unwittingly makes an enemy of another boy, Younger Bear. Younger Bear eventually owes his life to Jack when he saves Younger Bear's life. Jack is given the name "Little Big Man".

In 1865, Jack is captured by U.S. Cavalry troopers during a skirmish, and renounces his Cheyenne upbringing to save himself from being killed. Jack is put in the foster care of Reverend Silas Pendrake and his sexually frustrated wife, Louise, who tries to seduce Jack. After witnessing Mrs. Pendrake having sex with the soda shop owner, Jack leaves the Pendrake household and renounces his foster parents and religion.

In 1866, Jack becomes the apprentice of snake-oil salesman Meriweather. The two are tarred and feathered when their customers realize that Meriweather's products are fraudulent. One angry customer is Jack's now-grown sister Caroline, with whom he reunites. She attempts to mold her brother into a gunslinger named "the Soda Pop Kid". At a saloon, Jack meets Wild Bill Hickok, who takes a liking to him. When Hickok is forced to kill a man in self-defense, Jack loses his taste for gunslinging, and Caroline deserts him.

Jack becomes a partner in a general store and marries Olga, a Swedish woman. Jack's business partner turns out to be a thieving scoundrel. Cavalry officer George Armstrong Custer pays a visit. He suggests the couple restart their lives further west, and assures them they have nothing to fear from "Indians." The couple set out, but their stagecoach is ambushed by Cheyenne warriors, and Olga is abducted. Setting out in search of her, Jack is reunited with Old Lodge Skins and Younger Bear. Younger Bear has become a Contrary — a warrior who does everything in reverse. Jack makes friends with the Heemaneh Little Horse, but continues his search for Olga.

Jack becomes a "muleskinner" in Custer's 7th Cavalry, only because Custer incorrectly determines that was Jack's past job. He takes part in a battle against the Cheyenne, but when the troopers begin killing women and children, Jack flees. Jack is attacked by Shadow, who does not recognize him. Shadow is killed by a cavalryman, and Jack discovers Shadow's daughter Sunshine giving birth while hiding from the onslaught. He returns with her to Old Lodge Skins's tribe. Sunshine becomes his wife and bears him a child. Jack again encounters Younger Bear, who is now the henpecked husband of the long-lost Olga. Olga does not recognize Jack, who makes no attempt to make her remember him. Jack reluctantly takes in Sunshine's widowed sisters as wives, and agrees to father children with them.

In November 1868, Custer and the 7th Cavalry attack the Cheyenne camp at the Washita River. Jack saves the now-blind and elderly Old Lodge Skins, but Sunshine, their child, and her sisters are killed. Jack tries to infiltrate Custer's camp to exact revenge, but loses his nerve. Disheartened, Jack becomes the town drunk in Deadwood, South Dakota. While in a drunken stupor, he is recognized by Wild Bill Hickok, who gives him money to clean up. Hickok is shot and killed while playing cards and, with his last breath, asks Jack to bring money to a widow with whom he was having an affair. The "widow" turns out to be Louise Pendrake, now a prostitute. Jack gives her the money, but again rebuffs her sexual advances.

Jack becomes a trapper and hermit. His mind becomes unhinged after coming across an empty trap with a severed animal limb. While attempting suicide, he sees Custer and his troops marching nearby and decides to resume his quest for revenge. Custer hires Jack as a scout, reasoning that anything he says will be a lie, thus serving as a perfect reverse barometer.

In 1876, Jack tricks Custer into leading his troops into a trap at the Little Bighorn by truthfully telling Custer of the overwhelming force of Native Americans hidden in the valley. As his troops are slaughtered by the Sioux and Cheyenne, Custer begins to rave insanely. A wounded Jack tells him to shut up. Custer attempts to shoot him but is killed by Younger Bear, who then carries Jack away from the battlefield. Having thus discharged his life debt, Younger Bear announces that the next time they meet, he can kill Jack without becoming an evil person.[4]

Back at the Cheyenne camp, Jack accompanies Old Lodge Skins to the Indian burial ground, where the old man, dressed in full chief's regalia, decides to end his life with dignity. He offers his spirit to the Great Spirit, and lies down at his spot at the Indian Burial Ground to wait for death. Instead, it begins to rain. Old Lodge Skins is revealed to still be alive, and says, "Well, sometimes the magic works. Sometimes it doesn't." They return to his lodge to have dinner.[4]

Back in the present day, Jack ends his narrative story and dismisses the historian.

Cast

[edit]- Dustin Hoffman as Jack Crabb (a.k.a. Little Big Man)

- Faye Dunaway as Louise Pendrake (a.k.a. Lulu Kane)

- Chief Dan George as Old Lodge Skins

- Martin Balsam as Allardyce T. Meriweather

- Richard Mulligan as George Armstrong Custer

- William Hickey as the Historian

- Jesse Vint as Lieutenant

- Jack Bannon as Captain

- Jeff Corey as Wild Bill Hickok

- Jack Mullaney as card player

- Aimée Eccles as Sunshine

- Kelly Jean Peters as Olga Crabb

- Carole Androsky as Caroline Crabb

- Robert Little Star as Little Horse

- Cal Bellini as Younger Bear

- Thayer David as Reverend Silas Pendrake

- Ruben Moreno as Shadow That Comes in Sight

- Steve Shemayne as Burns Red in the Sun

- James Anderson as Sergeant

- M. Emmet Walsh as Shotgun Guard

Historical basis

[edit]The historical Little Big Man was a Native American leader bearing no resemblance to the Jack Crabb character. Little Big Man is known for his involvement in the capture and possible assassination of Crazy Horse at Fort Robinson in 1877.

The movie's portrayal of the Battle of Washita River as a Custer-led massacre of women and children (which Penn compares to the Holocaust) is not entirely accurate, as the camp was partially occupied by tribal warriors.[citation needed] The film, however, is consistent with historical records of other encounters between Indians and the U.S. Cavalry; the Cavalry's common tactic was to wait until the warriors had left the camp to hunt, or to lure the warriors away with assurances of good hunting, then to attack the unprotected village. The two massacre scenes are historically reversed; the Sand Creek massacre occurred first in 1864, in which Colorado militia (not including Custer) attacked a peaceful contingent of Native Americans, killing more than 150 women, children and elderly men. (The Sand Creek Massacre was depicted in another 1970 Western, Soldier Blue.) The Custer-led raid on the Washita occurred in 1868.

The film also presents an inaccurate representation of the death of Wild Bill Hickok. Hickok was actually killed nearly two months after the Battle of the Little Bighorn, on August 2, 1876, while playing poker at Nuttal & Mann's Saloon in Deadwood, South Dakota. Uncharacteristically, Hickok had his back turned to the door. At 4:15 p.m., Jack McCall walked in and shot Hickok in the back of the head. Hickok was famously holding two pairs — aces of uncertain suits and black eights — when he was shot, a set of cards thereafter called the "Dead Man's Hand".[8]

The film's depiction of Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer as a lunatic at the Battle of the Little Bighorn was intended as satire, although many of his quirks and vanities were inspired by contemporary observations. Custer's fatal tactics at the Little Bighorn were far more complex than portrayed in the film, which portrays him as having a searing hatred of Indians, and acting ruthlessly towards them in battle.[citation needed]

The character of Jack Crabb is partially based on Curley, one of Custer's Native American scouts from the Crow tribe. Curley rode with Custer's 7th Cavalry into the valley of the Little Bighorn, but was relieved of duty before the final attack, retreating to a nearby bluff to witness much of the action. Many conflicting stories of the era embellished Curley's participation, stating in several cases that he disguised himself with a Cheyenne blanket to escape the immediate field of battle. He was interviewed many times, with some writers claiming him to be the only surviving witness from the U.S. side of Custer's Last Stand. Curley gave several variations of his participation in the battle, and the accuracy of his later recollections has been questioned.[9] However, Thomas Leforge, who had recruited most of the Crow scouts for the event, maintained in Leforge's narrated biography that the claims were false, and that Curley neither took part as a scout had been expected to take part, nor claimed to have been in the battle.

Production

[edit]To obtain the hoarse voice of a 121-year-old man, Dustin Hoffman sat in his dressing room, screaming at the top of his lungs for an hour. The makeup for the ancient Crabb was created by Dick Smith from foam latex, and included revolutionary false eyelids that could blink along with the actor's. Due to editing, and much to Smith's chagrin, no blinks were visible in the finished film. Of the makeup, Hoffman was quoted in Life as saying, "I defy you to put on that makeup and not feel old".[10]

The role of Chief Old Lodge Skins was initially offered to Marlon Brando, Paul Scofield and Laurence Olivier, all of whom turned it down. The Little Bighorn battle scenes were filmed on location at Crow Agency, Montana, near the actual battle site. Some of the town scenes were filmed in Nevada City, Montana, a town that, by 1970, consisted predominantly of historic 19th-century buildings brought from elsewhere in Montana.

Aside from the Little Bighorn battle, all outdoor Indian scenes were filmed near Calgary, Alberta, Canada. Some interior and various other footage was shot on Hollywood sets. All Indian extras were North American Indians; although Aimée Eccles, who played Sunshine, is of British and Chinese descent,[11] and Cal Bellini, who played Younger Bear, was a Malay originally from Singapore.[12]

Old Lodge Skins dies at the end of the novel, but not in the film. In an interview, Arthur Penn explained the change: "We thought long and hard about this and in the first draft of the script he does die, but this death would have introduced an element of sadness into the film and we didn't want this. The film would have become dramatic, even melodramatic, instead of being picaresque. I also wanted to show that not only were the Indians going to be destroyed, but they were also condemned to live. On the whole, audiences like their entertainment dramatically compact and homogenous, but I want the opposite. A film should remain free and open, not with everything defined and resolved."[13]

Reception

[edit]Little Big Man received widespread acclaim from film critics. It was among AFI's 400 movies nominated to be on their list of America's greatest 100 movies.[5] On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 91% of 79 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 8/10. The website's consensus reads: "An ambitious tall tale that boldly meshes farce with historical tragedy, Little Big Man is both an amusing comedic showcase and a persuasive political statement."[14] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 63 out of 100, based on 7 critics, indicating "generally favorable" reviews.[15]

In his December 15, 1970, review, Vincent Canby of The New York Times called the movie, "Arthur Penn's most extravagant and ambitious movie, an attempt to capture the essence of the American heritage in the funny, bitter, uproarious adventures of Jack Crabb."[16] Roger Ebert, of the Chicago Sun-Times, agreed, giving the film four stars out of four, and describing Little Big Man as "an endlessly entertaining attempt to spin an epic in the form of a yarn".[17] Stanley Kauffmann of The New Republic wrote, "Arthur Penn has made a tangy and, I think, unique film with American verve, about some of the grisly things that American verve has done."[18]

Awards and nominations

[edit]Chief Dan George was nominated for an Academy Award as Best Actor in a Supporting Role. He won many honors for his performance, including the National Society of Film Critics Award and the New York Film Critics Circle Award. He was also nominated for a Golden Globe as Best Supporting Actor. Hoffman was nominated as Best Actor by the British Academy of Film and Television Arts. The screenplay by Calder Willingham was nominated for the Writers Guild of America Award as Best Drama Adapted from Another Medium. The film won a Special Mention at the 7th Moscow International Film Festival in 1971.[19]

In 2014, the film was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the Library of Congress, and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.[7][20]

Legacy

[edit]Arthur Hiller's 1984 comedy drama Teachers features Richard Mulligan partially reprising his Custer role as Herbert Gower, an outpatient from a mental institution who is accidentally put in charge of a U.S. history class. Gower teaches his pupils while impersonating historical figures, including Custer, but also Abraham Lincoln and Ben Franklin, among others.[21]

Actress Lily Gladstone, who is the first Indigenous person to win a Golden Globe award for acting,[22] has expressed admiration for Little Big Man, calling it a "great film".[23] However, she has also criticized the film's casting of Asian actors in Native American roles, which she interpreted as a means of likening the treatment of Indigenous peoples to American involvement in the Vietnam War. "That was absolutely an important talking point," she has stated, "but it was also Native history being used as a device to talk about something more political."[23]

Home media

[edit]As of 2016[update], Little Big Man has been released worldwide on VHS and DVD, and in the U.S. on a region-free Blu-ray.[citation needed]

In popular culture

[edit]The 2023 film The Holdovers, which is set in 1970, features a brief scene where Little Big Man is shown playing at the Boston Orpheum Theatre. During the scene, protagonist Paul Hunham, a classics professor portrayed by Paul Giamatti, remarks of the film, "You know, this is not only amusing, but for a movie, it's a fairly accurate depiction of life among the Cheyenne."

See also

[edit]- The Scarlet West (1925)

- General Custer at the Little Big Horn (1926)

- They Died With Their Boots On (1941)

- Frank Finkel

References

[edit]- ^ "Little Big Man, Box Office Information". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on February 3, 2012. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

- ^ a b "Little Big Man in 35mm". Timeline. Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

This epic revisionist Western plays out in flashback as recalled by Jack Crabb (Dustin Hoffman in extreme old age makeup by Dick Smith), a 121-year-old white man who was raised by the Cheyenne nation in the 1800s.

- ^ CLEARY, MICHAEL (1980). "Finding the Center of the Earth: Satire, History, and Myth in 'Little Big Man'". Western American Literature. 15 (3): 195–211. ISSN 0043-3462. JSTOR 43018396. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Rollins, Peter (2011). Hollywood's Indian: The Portrayal of the Native American in Film. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 121–136. ISBN 978-0813131658. Archived from the original on June 14, 2021. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- ^ a b c [1] Archived August 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Native Leaders of Canada - Dan George". www.newfederation.org. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ a b "Cinematic Treasures Named to National Film Registry". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ^ "Wild Bill Hickok is murdered — History.com This Day in History — 8/2/1876". History.com. August 5, 1953. Archived from the original on September 22, 2013. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- ^ "Curley is buried at Little Big Horn — History.com This Day in History — 5/23/1923". HISTORY. History.com. Archived from the original on September 22, 2013. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- ^ Life, November 20, 1970, volume 69 number 21, interview with Richard Meryman

- ^ Wood, Robin, "Arthur Penn," Praeger Film Library (1969), p. 120-123

- ^ Cal Bellini

- ^ Penn, Arthur (2008). Arthur Penn: interviews. University Press of Mississippi. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-60473-104-0. Archived from the original on June 14, 2021. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- ^ "Little Big Man". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved December 7, 2023.

- ^ "Little Big Man". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved December 7, 2023.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (December 15, 1970). "Little Big Man (1970)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 14, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Little Big Man". Chicago Sun Times. Archived from the original on July 8, 2010. Retrieved June 8, 2010.

- ^ "Stanley Kauffmann on films". The New Republic. December 26, 1970.

- ^ "7th Moscow International Film Festival (1971)". MIFF. Archived from the original on April 3, 2014. Retrieved December 23, 2012.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on December 17, 2014. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ "Reference to Mulligan reprising his Custer role in Teachers". IMDb.com. Archived from the original on January 5, 2013. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- ^ Zuckerman, Esther (January 8, 2024). "Lily Gladstone Becomes First Indigenous Person to Win a Golden Globe for Best Actress". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ^ a b "Lily Gladstone | Elevating Inspired Natives | Talks at Google", YouTube, Talks at Google, December 15, 2023, retrieved January 16, 2024

External links

[edit]- Little Big Man essay by Kimberly Lindbergs on the National Film Registry website

- Little Big Man at IMDb

- Little Big Man at the TCM Movie Database

- 1970 films

- 1970s American films

- 1970s Western (genre) comedy films

- American Indian Wars films

- American Western (genre) comedy films

- Cinema Center Films films

- Cheyenne in popular culture

- Cultural depictions of George Armstrong Custer

- Cultural depictions of Wild Bill Hickok

- English-language Western (genre) comedy films

- Films about Native Americans

- Films based on American novels

- Films based on works by Thomas Berger (novelist)

- Films directed by Arthur Penn

- Films set in 1859

- Films set in 1865

- Films set in 1866

- Films set in 1868

- Films set in 1876

- Films set in 1970

- Films set in Montana

- Films set in Oklahoma

- Films set in South Dakota

- Films shot in Alberta

- Films shot in Montana

- Native American cemeteries in popular culture

- Revisionist Western (genre) films

- United States National Film Registry films

- 1970s English-language films